To date, attention has mainly focused on forced labour in the private economy. But forced labour can be imposed by the State itself, perhaps as a systematic practice of punishing political dissidents or religious minorities. State imposed forced labour includes forced labour exacted by the military, compulsory participation in public works, and forced prison labour. The last category includes not only forced labour camps but also work imposed in semi-privatised or fully privatised prisons.

There are generally two distinct types of SIFL: compulsory labour by citizens, for example when national or local authorities force otherwise free citizens to work, perhaps during harvest season or as a means of mobilising labour for economic development; and work carried out by prisoners and detainees in breach of ILO Forced Labour Conventions. The exploitation of prison labour in some industrialised countries also constitutes forced labour, as prisoners in private prisons are expected to work for wages way below legal minimum wage.

Many companies are unaware of the use of state-imposed forced labour (SIFL) in their supply chains, but any business tainted by forced labour will not only suffer severe damage to their reputation, but could also be subject to litigation.

State-imposed forced labour

An estimated 4 million people were in state-imposed forced labour at any given point in time in 2016

When the ILO’s first instrument on forced labour was adopted in 1930, and even more so when the second instrument was adopted during the height of the Cold War in 1957, state-imposed forced labour was a major global issue and cause for concern. More recently, with the rise in the number of detected cases of forced labour imposed by private actors, much of the concern has shift- ed away from that imposed by States. Nevertheless, with some 4 million per- sons affected, state-imposed forced labour remains a major problem.

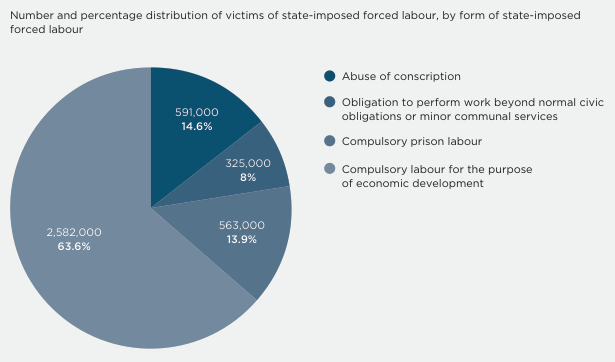

Of the total number of people in state-imposed forced labour, the majority (64 per cent) were forced by their government to work for the purpose of furthering economic development. How- ever, while the overall number and percentage appears high, only a few States actually resort to this kind of forced development work. Fifteen per cent of those in state-imposed forced labour were subjected to abuse of conscription and 14 per cent were forced to carry out prison labour under conditions that violate the pertinent ILO standards. The remaining 8 per cent were either forced to perform work or services going beyond normal civil obligations, or to perform communal services exceeding the nature and scope of these activities as permit- ted by the ILO standards. The share of men in forced labour imposed by state authorities is higher than that of women, essentially because more men than women are affected by abuse of conscription and prison labour in all concerned countries.

Children represented 7% of victims of state-imposed forced labour

The main forms of forced labour in which state authorities were found to use children were in the abuse of the obligation to participate in minor communal services or civic obligations and, to a certain extent, in work for purposes of economic development. More than half the forced labourers in the former category were children, specifically North Korean children who are compelled as part of their schooling to engage in work that far exceeded the goals of vocational education and was also highly demanding in physical terms. Globally, few children were found in forced prison labour, or in abuse of conscription, although data gaps in these areas remain large. The forced recruitment of children by armed groups and armed forces was excluded from the estimates due to a lack of reliable data.

Forced labour imposed by the state varied considerably in terms of duration

Among cases of forced labour imposed by state authorities, not only the type of work varies widely, from picking cotton to constructing roads, but so does the length during which victims are exploited. A typical case of short duration, generally a few weeks, is found in States that requisition their citizens for the purpose of economic development work, such as the forced participation of students, unemployed, or any individual in public construction, industrial, or agricultural projects. This is also the case for the abuse of communal services where a large share of a population is forced to perform “community work” that is not for the benefit of their communities and has not been decided upon by members of those communities. In these cases, the forced labour usually involves a large group of citizens for a few days per month. On the other end of the spectrum, some countries force military con- scripts to perform non-military tasks for a number of years. And forced labour in prison varies between a few weeks for cases of people in administrative detention to many years for long term sentences.

Forced prison labour

Forced prison labour deserves separate treatment. The ILO Conventions establish broad principles regarding the conditions in which prisoners can or cannot be required to work; and, in cases where they are required to work, the limitations on private sector involvement in prison labour.

Generally, prisoners who have been duly sentenced by a court of law can be required to work. They cannot be required to work be- fore sentencing, or when they are in administrative detention. And even if prisoners have been sentenced by a court of law, they cannot be required to work if they have been imprisoned for a range of ideological, political, and other reasons specifically mentioned in the ILO’s Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105). Moreover, there need to be specific guarantees of protection for prisoners placed at the disposal or private individuals, companies, or associations, including those confined in private prisons. In the latter case, guidance has been provided by ILO supervisory bodies on factors to ensure that labour is provided voluntarily and not under the menace of any penalty.

Of the 563,000 persons estimated to be in forced prison labour, 202,000 are in administrative detention centres. While the administrative imposition of imprisonment involving forced labour appears to have declined in recent years, a number of countries in East and South- East Asia have responded to the rise in substance abuse by establishing laws and policies that allow for compulsory detention without trial in a court of law, and the imposition of compulsory labour, as a means of treatment for persons suspected of being dependent on drugs. Re- ports on such “rehabilitation centres” in several countries have highlighted the lack of due process and legal assistance.

Additionally, in some cases, migrants and refugees have also been forced to work when confined in detention centres pending administrative processing.

The use of forced prison labour for political and other impermissible reasons is particularly difficult to assess. There is, not surprisingly, no available data on penal sanctions imposed on political activists, journalists, or members of dissident groups in repressive regimes.

Nor are statistics generally available concerning the various ways in which private companies can be involved in or benefit from compulsory prison labour. It is now generally recognised that the private use of prison labour (either through privatised prisons or through contracts between public prison agencies and private companies) is widespread in certain countries and can provide significant revenue for the private agencies concerned. There have been pol- icy debates in a number of countries since the first steps were taken as of the 1980s to seek more private sector involvement in prison administration. Proponents of private sector involvement in prison industries argue that this can reduce incarceration costs and contribute to rehabilitation. Opponents argue that it can increase exploitation, and that the authority for punishment is a core government function that should not be delegated to the private sector. Furthermore, in most cases, labour and social security laws are not applied to prisoners, meaning that prison labour can constitute unfair competition with free labour.

On this subject, there has been substantial dialogue between the ILO supervisory bodies and those Member States that have ratified the first forced labour Convention. The supervisory bodies have pointed to the need for convincing indicators that the choice to work is voluntary.

IMAGE CREDIT: WikiCommons / By Laogai Research Foundation - Laogai Research Foundation, CC BY 3.0,