The first Global Study on Smuggling of Migrants from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) list the following trends developing in respect of people smuggling:

Migrants are smuggled in all regions of the world

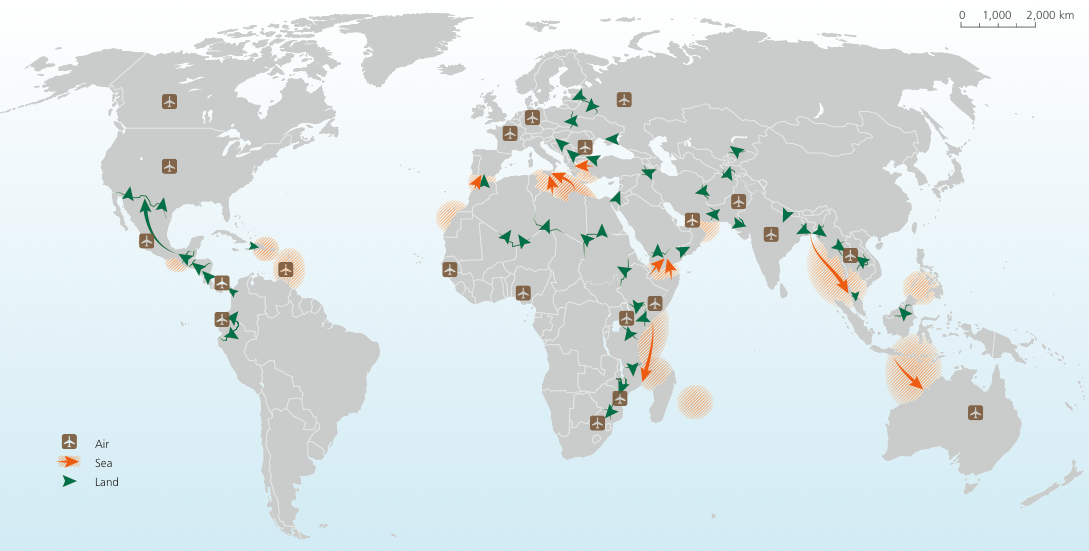

Smuggling of migrants affects all regions of the world. Different areas are affected to varying degrees. This Study describes some 30 smuggling routes, from internal African routes towards North and Southern Africa, to Asian routes towards Europe and the Middle East, or to wealthier countries in South-East Asia and the Pacific. From the Mediterranean sea routes, to land routes between Latin America and North America; and from the myriad air passages usually undertaken with counterfeit or fraudulently obtained documents, to hazardous overland journeys across deserts and mountains.

Smuggling of migrants is a big business with high profits

There is evidence that, at a minimum, 2.5 million migrants were smuggled for an economic return of US$5.5-7 billion in 2016. This is equivalent to what the United States of America (some US$7 billion) or the European Union countries (some US$6 billion) spent on humanitarian aid globally in 2016. This is a minimum figure as it represents only the known portion of this crime.

The smugglers’ profits stem from the fees they charge migrants for their services. The fees are largely determined by the distance of the smuggling trajectory, number of border crossings, geographic conditions, means of trans- port, the use of fraudulent travel or identity documents, risk of detection and others. The fees are not fixed, and may change according to the migrants’ profiles and their perceived wealth. For example, Syrian citizens are often charged more than many other migrants for smuggling along the Mediterranean routes (an extra charge that may or may not lead to a safer or more comfortable journey).

Major land, sea and air smuggling transits and destinations

Supply and demand

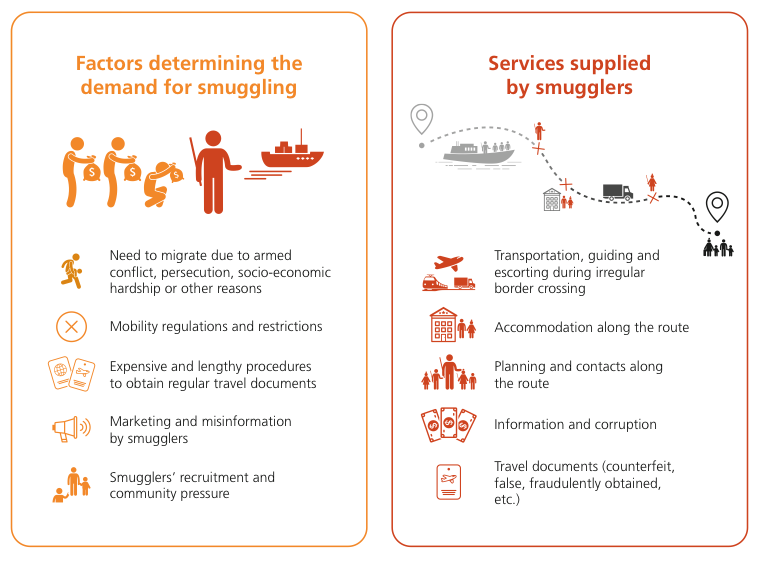

Smuggling of migrants follows the same dynamics of other transnational organised crime markets. It is driven by a demand and a supply of smuggling services to circumvent existing regulations. The many smugglers who are pre- pared to offer services to facilitate irregular border cross- ings represent the supply of services.

From the supply side, smugglers’ proactive recruitment and misinformation increase the number of migrants who are willing to buy smuggling services. Smugglers advertise their business where migrants can be easily reached, such as in neighbourhoods home to diaspora communities, in refugee camps or in various social networks online. Demand for migration is determined by socio-economic conditions, family reunification as well as persecution, instability or lack of safety in origin countries. Demand for smuggling services is determined by the limited legal channels that cannot satisfy the total demand for regular migration or by the costs of legal migration that some migrants cannot afford. Demand for smuggling services is particularly high among refugees who, for lack of other means, may need to use smugglers in order to reach a safe destination fleeing their origin countries.

Routes change

Geography, border control, migration policy in destination countries, smugglers’ connections across countries and cost of the package offered by smugglers are among the key factors that determine the routes and the travel methods. When geography allows, land routes are widely used, more than sea or air smuggling routes that generally require more resources and organization. The vast majority of migrants smuggled from the Horn of Africa to Southern Africa, for example, use land routes. In recent years, among some 400 surveyed migrants, some 10 per cent travelled by air, while only 1% travelled by boat.

Measures to increase or decrease border control with con- sequent increased or decreased risks of detection for smuggled migrants, if taken alone, typically lead to rapid route displacement rather than changes in the overall number of smuggled migrants. Stricter border control measures often increase the risks for migrants and provide more opportunities to profit for smugglers.

During the period 2009-2015, for example, a large part of the recorded smuggling activity between Turkey and the European Union shifted from land passages to sea crossings, in response to increased controls at different borders. Similar examples are the shifts in the smuggling activities across the Red Sea or the Arabian Sea from the Horn of Africa to the Arab peninsula or smuggling to Spain along the Western Mediterranean route. In the latter case, arrivals at the different destination areas in Spain (Canary Islands, Ceuta, Melilla, the Andalusian coast) have fluctuated significantly in recent years, often in response to enhanced enforcement activities.

Hubs are stable

While routes may change, smuggling hubs, where the demand and supply of smuggling services meet, are rather stable over time. Hubs are key to the migrant smuggling crime. They serve as meeting places where disparate routes converge and arrangements are made for subsequent travel. Often, the locations of smuggling hubs are capitals or large cities, although they may also be remote towns where much of the economic activity is linked to migrant smuggling. Agadez in Niger, for example, is a transit for current smuggling flows, with hundreds of thousands having organised their trip from West Africa to North Africa (and Europe) there. Already in 2003, some 65,000 migrants were reported to have left Agadez for North Africa.

Smugglers are often ethnically connected to smuggled migrants or geographically linked to the smuggling territory

There are some large, transnational organisations involved in smuggling that may or may not have ethnic linkages with the territory where they operate or the migrants they smuggle. As a general pattern, smaller-scale smugglers are either ethnically linked to the territories where they operate, or they share ethnic or linguistic ties with the migrants they smuggle. Smugglers who are in charge of recruiting, promoting and selling smuggling packages normally market their activities to people from the same community or same ethnic group, or at least the same citizenship. Smugglers in charge of facilitating the actual border cross- ing have extensive knowledge of the territory to be crossed and the best methods to reach the destination.

Ethnic and/or linguistic ties between smugglers and migrants is one of the elements that often brings migrants and smugglers together. A reliable connection is key in a market that is unregulated by definition. When demand- ing smuggling services, migrants seek well-reputed smugglers. In presenting their offer, smugglers aim to establish a relationship of trust with migrants. The pressing need for migrants to move and the vast information gaps seem, however, to impede migrants from making an informed decision. As a consequence, migrants try to reduce these information gaps by relying on the opinion of their communities, relatives and friends, and more recently, social media.

The organization of migrant smuggling

The organization and size of smuggling operations vary. Some smugglers provide limited small-scale services such as a river crossing or a truck ride. These smugglers usually operate individually, and on an ad hoc basis. Some of the migrants who were successfully smuggled turn themselves into smugglers.

The profits of these small-scale smugglers are typically not substantial, but entire communities may depend on the income from these “low-level” services, particularly in some border and transit areas. In these types of communities, smuggling-related activities may range from cater- ing to providing telecommunication services for migrants en route to their destination.

Smugglers may also be organised in loose ‘networks’ which do not involve strict hierarchies. Participants operate with much autonomy in different parts of the smuggling process, for instance, facilitating a certain border crossing, recruiting a particular group of migrants, counterfeiting documents or preparing vessels for sea smuggling. They do not work exclusively with only one smuggling network and the links are similar to business relations. Smugglers with ‘broker’ functions play key roles in this system as they are able to maintain these different smuggling actors at easy reach.

Other smugglers belong to large and well-organised hierarchical criminal operations with transnational links and the capability of organising sophisticated smuggling pas- sages that might involve the use of falsified or fraudulently obtained travel documents. Often, such smuggling is sold as ‘packages’ that involve migrants travelling long distances, using multiple modes of transportation.

Smugglers, other criminal organisations and corruption

Generally, smuggling networks seem not to be involved in other forms of major transnational organised crime. In some parts of the world, however, smuggling networks have links with large violent criminal organisations that they have to pay for the ‘right’ to safe passage for migrants, for example, along the border between the United States and Mexico. In other cases, smugglers may hand over migrants to such groups for extortion of ransom, robbery or other exploitation.

Many smuggling networks engage in systematic corruption at most levels; from petty corruption at individual border control points to grand corruption at higher levels of government. Corrupt practices linked to migrant smuggling have been reported along nearly all the identified routes.

Smuggled migrants are mainly young men but unaccompanied children are also smuggled

Most smuggled migrants are relatively young men. That is not to say that women and children are not smuggled or do not engage in smuggling. On some routes, notably in parts of South-East Asia, women comprise large shares of smuggled migrants. The gender composition of smuggled migrant flows may also be influenced by the circumstances driving their mobility. Among Syrian smuggled migrants – most of whom are escaping from armed conflict – there are many families, whereas this is less commonly reported among other groups of smuggled migrants.

Many smuggling flows also include some unaccompanied or separated children, who might be particularly vulnerable to deception and abuse by smugglers and others. Sizeable numbers of unaccompanied children have been detected along the closely monitored Mediterranean routes to Europe and the land routes towards North America, though it may also be a significant concern elsewhere.

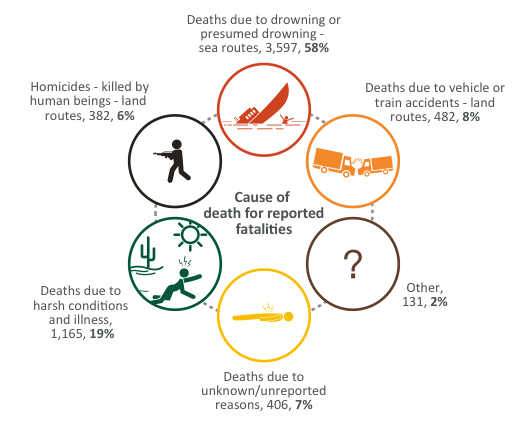

Migrant smuggling can be deadly

Every year, thousands of migrants die during smuggling activities. Accidents, extreme terrain and weather conditions, as well as deliberate killings have been reported along most smuggling routes. Systematic killings of migrants have also been reported, making this a very violent illicit trade. The reported deaths – most of them along sea smuggling routes - represent only the tip of the iceberg of the ultimate human cost suffered by smuggled migrants. Many migrant deaths are likely to go unreported, along unmonitored sea routes as well as remote or inhospitable stretches of overland routes.

In addition to fatalities, smuggled migrants are also vulnerable to a range of other forms of crime. Some of the frequently reported types faced by smuggled migrants include violence, rape, theft, kidnapping, extortion and trafficking in persons. Such violations have been reported along all the smuggling routes considered. In addition, smugglers’ quest for profit may also lead them to neglect the safety of migrants during journeys. For example, smugglers may set off without sufficient food and drink, the vehicles they use might be faulty, and migrants who fall ill or are injured along the way might not receive any care.

Number of migrant fatalities reported, by cause of death, 2017