“I was looking for a job.” - This is often how a slavery survivor’s story begins.

The problem of modern slavery persists and it is the second most lucrative criminal trade in the world, after narcotics. In South Asia alone, there are thought to be almost 12 million people working in conditions of modern slavery, most subject to bonded labour practices. The $150 billion that is generated by modern slavery every year is recycled into other criminal enterprises and is used to further reinforce corruption and undermine democracy, transparency and the rule of law around the world. Thus far, efforts to impose greater oversight and accountability on the actions of abusive employers have been timid.

At root, the problem of modern slavery is very simple: it is the exploitation of the weak and vulnerable by the strong and powerful. If the strong and powerful genuinely wanted to change the systems that lead to modern slavery, they could do so.

Modern slavery can affect people of any age, gender or race. However, most commonly, slavery affects people and communities who are vulnerable to being taken advantage of. It can be someone living in poverty and having no real prospects for a decent job, who will accept a good sounding offer of a job abroad that turns out something else that what was promised.

It can be someone from a community heavily discriminated against, such as Dalits in India, who will have to borrow money for a medical treatment from a wealthy farmer, and will fall into debt bondage for decades with no hope of help from corrupted authorities.

Or it might be a young girl who happens to live in a society where early marriage is completely acceptable, who will have no choice over marrying an older man.

Or it might be someone who happens to be born to a mother coming from a ‘slave’ cast, literally owned by their masters from the day they are born.

Slavery is also more likely to occur where the rule of law is weaker and corruption is rife. It can also happen to groups of people who are not protected by the law, for example migrants whose visa status is irregular are easy to blackmail with deportation.

Findings from the 2018 Global Slavery Index highlight the connection between modern slavery and two major external drivers - highly repressive regimes, in which populations are put to work to prop up the government, and conflict situations which result in the breakdown of rule of law, social structures, and existing systems of protection.

The country with the highest estimated prevalence is North Korea. In North Korea, one in 10 people are in modern slavery with the clear majority forced to work by the state. As a UN Commission of Inquiry has observed, violations of human rights in North Korea are not mere excesses of the state, they are an essential component of the political system. This is reflected in the research on North Korea undertaken through interviews with defectors for this Global Slavery Index. North Korea is followed closely by Eritrea, a repressive regime that abuses its conscription system to hold its citizens in forced labour for decades. These countries have some of the weakest responses to modern slavery and the highest risk.

The 10 countries with highest prevalence of modern slavery globally, along with North Korea and Eritrea, are Burundi, the Central African Republic, Afghanistan, Mauritania, South Sudan, Pakistan, Cambodia, and Iran. Most of these countries are marked by conflict, with breakdowns in rule of law, displacement and a lack of physical security (Eritrea, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Afghanistan, South Sudan and Pakistan). Three of the 10 countries with the highest prevalence stand out as having state-imposed forced labour (North Korea, Eritrea and Burundi). Indeed, North Korea, Eritrea, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Afghanistan, South Sudan and Iran are the subject of various UN Security Council resolutions reflecting the severity and extremity of the situations there.

The most common causes of modern slavery are:

Absence of the rule of law

Slavery thrives in the absence of a properly functioning law enforcement system. It is often abetted by police and other authorities. Without adequate enforcement of existing laws and the strengthening of legal frameworks, human traffickers operate with impunity.

Example: Democratic Republic of Congo

The fractured government of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) has left large groups of people vulnerable to slavery. Decades of ethnic and political turmoil have been compounded by weak governance structures and large displaced populations. There are more than 473,000 refugees and 3.9 million internally displaced people in the DRC. The huge central African nation has also faced an influx of migrants, predominantly from its eastern neighbours. Eastern Congo is dominated by dozens of domestic and foreign-backed militias, which wield power over much of the country’s lucrative natural resources. The DRC is the world’s largest producer of cobalt and also has vast reserves of gold, diamonds, coltan, tin, tantalum, and tungsten. Many of these minerals are critical components of laptops, smart phones, and other consumer electronics. These natural resources have created a profit motive for traffickers and militias to exploit vulnerable communities. Large consumer demand for cheap electronics drives illicit mining activities, experts say.

Insurgent groups in the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu, Ituri, Maniema, and Tanganyika occupy territory with fertile land and illegal artisanal mines. By some estimates, there are between five hundred thousand and two million artisanal miners in eastern Congo. Overall, extractive industries, such as mining, account for 22 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP). Refugees and Congolese have been forced to work the mines.

Amid civil war, women and children have been the victims of sexual slavery, rape has been used as a weapon, and boys have been forced to serve as soldiers in armed groups. The DRC’s protracted conflicts and limited resources have made combating slavery all the more difficult. Corruption and patronage networks run deep, and politicians and the military have links to armed groups.

Population boom

The world’s population rose from 2.5 billion in 1950 to nearly 7.4 billion in 2015. The world is also in a state of historic flux: a record-setting 65.6 million people were displaced at the end of 2016 by war and persecution, and still more by economic uncertainty and environmental destruction. China and India, the two most populous nations, have lifted millions out of poverty, yet millions more in both countries remain marginalised and are susceptible to abuse. In dire straits, displaced people seek out perilous employment and are vulnerable to false offers. Traffickers prey upon the multitude of displaced people.

Poverty

About 765 million people worldwide live in extreme poverty, making less than $1.90 per day. Those in destitute conditions have limited means to support their families. In the absence of alternatives, many people, taking risks, are lured by sham offers of better futures.

However, poverty alone does not explain slavery. Roughly 700 million people meet the threshold of extreme poverty, making less than $1.90 per day of income and the number of slaves is estimated to be 40 million. What distinguishes these 40 million from the other 700 million of the very poor? Slavery usually occurs when poverty is compounded by specific risk factors.

These include an inability to assert basic human rights, lack of access to essential social and economic services (especially schools, health care and credit); the failure of the rule of law; and, an absence of services for slavery survivors that leads to re-enslavement.

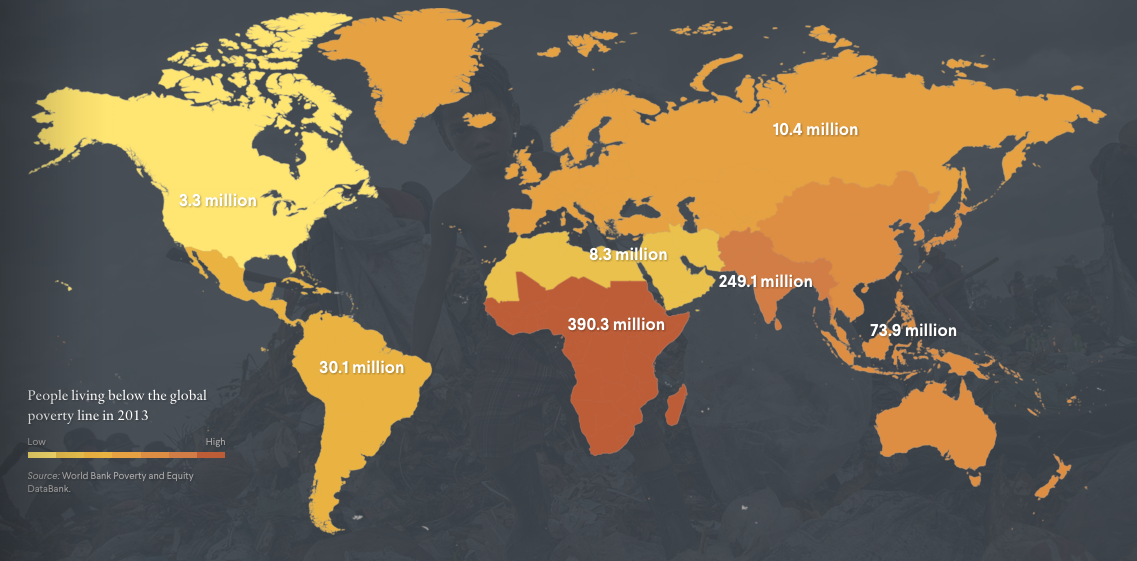

People living below poverty line

Marginalised groups

Groups that face discrimination, including ethnic and religious minorities, women and children, and migrants and refugees, are vulnerable to enslavement. At particular risk are those fleeing war and armed conflict, such as the Yazidi minority in Iraq and Syria, and Myanmar’s Muslim Rohingya population.

Example: Thailand

The fishing industry in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand, has been notorious for severe labor abuses. With eleven of the world’s largest fisheries in Asia, labor is in heavy demand. These mega fisheries often employ migrants from Bangladesh, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

The majority of Thailand’s fish harvest (mostly shrimp and tuna) is exported to Asian, European, and American markets. The industry, which brings in more than $7.3 billion annually, suffers from a labor shortage. Fishing, processing, and packaging firms have come to rely on migrant labor provided by illicit networks, whose recruiters often falsely promise high-paying jobs in regulated industries. Migrants, who account for 5 to 10 percent of the Thai workforce, sometimes must work years to pay back illegal recruitment fees.

Those employed in the Thai fishing industry are often subject to exploitation and abuse, including unclear contracts, withheld wages, and dangerous working conditions. Escapees have reported threats of violence, beatings, and sexual abuse, as well as the execution of their shipmates.

Collusion between police and traffickers has impeded efforts to address forced labor in the Thai fishing industry. Despite crackdowns by federal authorities, police and provincial administrations have been accused of accepting bribes from labor smugglers.

War and conflict

Instability brought on by war or conflict can expose besieged communities to forced labor networks.

Examples: Iraq and Syria

The rise of the self-proclaimed Islamic State and violence in Iraq and Syria have left residents of many communities at risk of capture or enslavement. When Islamic State forces overran towns populated by the Yazidi ethnoreligious minority in northern Iraq in 2014, they captured thousands of Yazidis and displaced an estimated 360,000 [PDF]. Hundreds of thousands fled, while thousands were kidnapped or killed by militants. During their occupation of these areas, which ended in 2017, militants instituted slavery involving the sexual exploitation of women and girls. (They have done the same to Christians and other minorities.) Some Yazidis were promised jobs, while others were kidnapped or captured as territory fell to the Islamic State. As the militants were ousted from occupied territories, additional horror stories of the enslavement of Yazidi women and girls emerged.

Yazidi women and girls as young as eight were forced into sexual slavery, sold in markets or gifted by commanders to fighters as brides. Some were sold at prices between $200 and $1,500. Captives were also forced into domestic servitude, cooking, cleaning, and, at times, raising children. Islamic State extremists enslaved 6,417 Yazidis, according to the Kurdistan Regional Government. An estimated three thousand Yazidis remained captive as of September 2017, according to the United Nations.

While many Yazidi men have been executed, young boys have been forced to convert to Islam and placed in indoctrination and military training camps. The United Nations described the recruitment and use of children in combat in Syria by the Islamic State, as well as by other parties to the conflict, as “commonplace.” Those who refused or attempted to escape suffered beatings, torture, rape, or execution.

Natural disasters

Weather patterns are increasingly unpredictable, and climate catastrophes, such as monsoons and earthquakes, have become more common. Extreme weather, as well as resulting pandemics, can ravage a country’s physical infrastructure, displace communities, and increase the desperation of already marginalised groups.

Example: Haiti

Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas, has suffered from extraordinary natural disasters, including devastating rainfall, hurricanes, and severe earthquakes. They have exacerbated poor governance stemming from regime changes and political instability, hampering efforts to combat slavery.

Among those most at risk are the restavek, children whose parents cannot support them and who are sent from rural areas to live in the homes of relatives or other families in cities. The Haitian Creole word, derived from French, means “to stay with,” and the process has become embedded in Haitian culture. These children often find themselves trapped in domestic servitude.

About 286,000 children, mostly girls under the age of fourteen, work as domestic servants, according to a 2015 report. These children are made responsible for household chores—cleaning, cooking, washing clothes, fetching water—and are often subject to physical abuse and malnutrition. As adults, former restaveks lack education, skills, and aspirations, leaving them once again vulnerable to trafficking. Some resort to begging, prostitution, or crime to support themselves.

Trafficker’s motives

Greed drives the modern slave trade. “This is an economic crime,” said Kevin Bales, a leading expert on contemporary slavery, in a TED Talk. “People do not enslave people to be mean to them; they do it to make a profit.”

IMAGE CREDIT: ILO